Brush-Everard House Archaeological Report, Block 29 Building 10 Lot 165-166-172Originally entitled: "Archaeological Excavations on The Brush-Everard Property an Interim Report"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1580

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS

ON THE BRUSH-EVERARD PROPERTY:

AN INTERIM REPORT

Department of Archaeological Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

December 1989

| Introduction | 1 |

| Summary of Property History | 3 |

| Previous Archaeological Investigations | 6 |

| Brush-Everard House | 7 |

| Outbuildings | 7 |

| Kitchen | 8 |

| Smokehouse | 9 |

| Potting Shed or Office | 9 |

| Laundry | 10 |

| Wellhouse and Dairy | 10 |

| Palace Power Plant and Pond Area | 10 |

| 1987-1989 Archaeological Results | 12 |

| Pre-House (Middle Plantation Period, 1633-1699) | 12 |

| Borrow Pit | 13 |

| Slot Fence | 14 |

| John Brush Period, 1717-1727 | 15 |

| Privy | 16 |

| Ravine fill | 20 |

| Interim Period, 1727-1756 | 22 |

| Gilmer Trash Pits | 22 |

| Post Structure | 24 |

| Thomas Everard Period, c. 1751/6-1781 | 26 |

| Post-18th Century | 29 |

| Polly Valentine House | 29 |

| Jefferson Bone Handle | 30 |

| Summary | 32 |

| Bibliography | 35 |

| Figure 1. Frenchman's Map superimposed over current landscape map, showing locations of 18th-century structures | 1 |

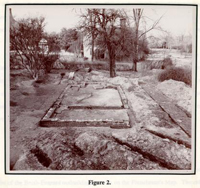

| Figure 2. Archaeological cross-trenching on the Brush-Everard property in 1946 | 6 |

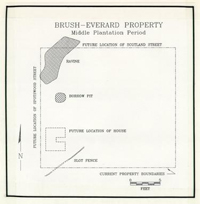

| Figure 3. Middle Plantation period figures on the Brush-Everard property | 13 |

| Figure 4. John Brush period structures and features on the Brush-Everard property | 15 |

| Figure 5. Foundations of the early 18th-century privy on the Brush-Everard property | 16 |

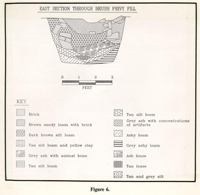

| Figure 6. East section of privy pit fill | 17 |

| Figure 7. English delftware cups from the privy | 18 |

| Figure 8. Delftware plate from the privy | 19 |

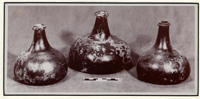

| Figure 9. Pint bottles recovered from the privy | 19 |

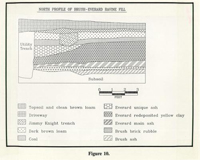

| Figure 10. Profile of the ravine fill on the Brush-Everard property | 21 |

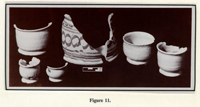

| Figure 11. Delftware drug jars and ointment pots from Gilmer trash pits | 23 |

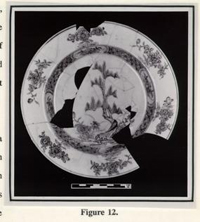

| Figure 12. Chinese porcelain from the Gilmer period trash pits | 24 |

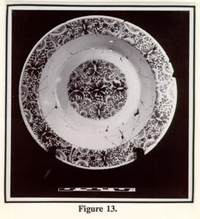

| Figure 13. Delftware bowl from Thomas Everard ravine layers | 27 |

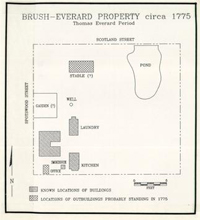

| Figure 14. Thomas Everard period structures and features | 28 |

| Figure 15. Foundations of the Mammy Polly Valentine house | 29 |

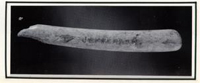

| Figure 16. Thomas Jefferson knife handle | 30 |

| Figure 17. Engraving on the Thomas Jefferson knife handle | 31 |

INTRODUCTION

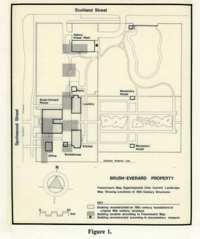

During the summers of 1987 through 1989, the Department of Archaeological Research conducted an investigation of the north and south yards of the Brush-Everard property (Figure 1). This project, funded by a grant from AT&T, was sought to identify clues of slave daily life and evidence of slave housing in 18th-century Williamsburg. The

Figure 1.

2

Brush-Everard property was chosen for this research because its principal resident, Thomas Everard, Clerk of York County and mayor of Williamsburg, owned at least seven slaves during his tenure on the property in the third quarter of the 18th century. The 1781 Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg shows two structures, believed to have been a stable and coach house, in the yard north of the house. These structures, which could have served additionally as slave housing, had not been located through archaeological cross-trenching done in the 1940s. One of the goals of the 1987 excavation was to re-excavate this area in hopes of finding postholes, brick piers, robbed foundation trenches, or any other traces of the buildings that the earlier excavation may have overlooked. Excavations proceeded at the Brush-Everard property, with the assistance of participants enrolled in our Learning Weeks in Archaeology program and students enrolled in the joint William and Mary/Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archaeological Field School.

Figure 1.

2

Brush-Everard property was chosen for this research because its principal resident, Thomas Everard, Clerk of York County and mayor of Williamsburg, owned at least seven slaves during his tenure on the property in the third quarter of the 18th century. The 1781 Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg shows two structures, believed to have been a stable and coach house, in the yard north of the house. These structures, which could have served additionally as slave housing, had not been located through archaeological cross-trenching done in the 1940s. One of the goals of the 1987 excavation was to re-excavate this area in hopes of finding postholes, brick piers, robbed foundation trenches, or any other traces of the buildings that the earlier excavation may have overlooked. Excavations proceeded at the Brush-Everard property, with the assistance of participants enrolled in our Learning Weeks in Archaeology program and students enrolled in the joint William and Mary/Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archaeological Field School.

SUMMARY OF PROPERTY HISTORY

Like most of the properties located within the confines of the colonial town limits of Williamsburg, the Brush-Everard lots have experienced a long and varied history. What follows will be a summary of the property history. For a more complete discussion, see Stephenson (1956).

John Brush purchased Lots 165 and 166 in 1717, and in compliance with the Building Act of 1705, had constructed a frame house (20' x 44' 2") by 1719. Brush, a gunsmith, retained lots 165 and 166 until his death in 1726 at which time the property passed into the hands of his unmarried daughter, Elizabeth Brush, and his son-in-law, Thomas Barbar.

Elizabeth Brush subsequently sold her share of the property to Thomas Barbar in 1727. When Barbar died a few months later, in May of 1727, his wife sold the property to Mrs. Elizabeth Russell in 1728. Most likely, Elizabeth Russell married Henry Cary, 11, because in 1742, he and his wife, Elizabeth, conveyed Lots 165 and 166 to William Dering. Dering, a dancing teacher and an artist, mortgaged this property in 1744 to Bernard Moore and Peter Hay to secure a debt to William Prentis. Philip Lightfoot later took over this mortgage, and when he died in 1749, his son, William Lightfoot assumed responsibility. Dering apparently moved to Charleston in late 1749, and ownership of this property is uncertain between 1751 and 1779. It may have been purchased in 1751 at an "outcry' by Thomas Everard or John Blair. Archaeological evidence suggests that Thomas Everard may have lived on lots 165 and 166 as early as 1756, when he sold his property on 4 Nicholson Street to Anthony Hay (Frank 1967). By 1779, deed books show Everard as owning lots 165, 166, and 172. Lot 172 was purchased in 1773; but as yet, no records have been found to date the purchase of Lots 165 and 166.

After Everard's death in 1781, John Stith was taxed for the three lots formerly belonging to Everard. Dr. Isaac Hall owned the property between 1787 and 1788, and then conveyed it to Dr. James Carter. After 1798, the property was taxed to James Carter's estate.

Land tax records between 1820 and 1830 charge the lot and buildings to Milner Peters. From 1830-1847, Dabney Browne owned the property, which he transferred to Daniel Curtis in 1847. Curtis conveyed this property to Sydney Smith in 1849. The property remained in the Smith family until W. A. R. Goodwin purchased it in 1928 for the Williamsburg Restoration. Between 1949 and 1952, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation restored the Brush House and its outbuildings.

The Frenchman's Map (1782) shows six structures on lots 165 and 166 at the end of the 18th century, of which three have been explored through archaeological investigations and reconstructed or restored (Figure 1). The house, built between 1717 and 1719 by John Brush, was enlarged by the addition of two eastern wings, probably during Thomas Everard's occupation of the property. Around 1780, the southeast wing of the Brush-Everard House was destroyed and a somewhat smaller, modem wing was in place there at the time of the house restoration. Photographs show the colonial foundation extending approximately 6' east of the modern wing.

5The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation purchased the Brush-Everard House in 1928, including in the deed a life-tenancy agreement with its former owners, Misses Estelle and Cora Smith. As the Smith sisters would allow no restoration to take place during their lifetime, the house was not restored until 1947/48.

PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has sponsored two previous excavations of the Brush-Everard property. The first of these was undertaken in 1947, prior to the restoration of the house, under the direction of James Knight. Excavation took place around the house, as well as in the vicinity of the various outbuildings on Lots 165, 166 and 172. Photographs from the excavation show the cross-trenching typical of Knight's excavations (Figure 2). The second archaeological investigation, conducted in 1967 by Ivor Noel Hume, focused on the area around the Brush-Everard kitchen and smokehouse.

7Brush-Everard House

Archaeology around the east side of the house revealed the foundations of an earlier wing, similar in size to the standing north wing. This south wing thus gave the house an U-shaped plan in the late 18th century. At the time, it was believed that Thomas Everard had constructed the two east wings on the house soon after his purchase of the property, sometime in the third quarter of the 18th century. Recent tree ring dating in the north wing places its construction date at around 1720, however, indicating that at least that wing was constructed by John Brush. The 1947 excavations around the house uncovered the brick remains of an earlier front entrance. The porch appeared to have possessed a pilastered pediment similar to that of the Grissell Hay House. Although this most likely did not represent the structure's original porch, no other entrance remains were discovered.

A great deal of brick paving, and several walkways at the rear of the house were revealed approximately 1' below grade. One of the walkways ran east into the boxwood garden; and another ran west from the kitchen door to Palace Green. Several marl walks were also uncovered in the front and on the north side of the house. This brick paving represents the most extensive use of paving in Williamsburg, and has been reconstructed as revealed through archaeological excavation.

Outbuildings

Archaeological excavations in 1946/47 also concentrated on locating the structural remains of the Brush-Everard outbuildings as seen on the Frenchman's Map. The colonial 8 period kitchen was still standing to the east of the house; as was an old smokehouse, believed to be original.

Kitchen

The existing kitchen at the Brush-Everard House is a brick structure measuring 28' 7 ½" x 17', with a large brick chimney on the south end. It is the only extant 18th-century brick kitchen in Williamsburg. Initially constructed as a frame structure around 1730, it was altered twice during the 18th century. Archaeological excavations were conducted at the kitchen in 1946-47, and again in 1967.

The 1946/47 excavations took place around the exterior foundation walls and located evidence that the kitchen was originally a frame structure. The existing chimney, the south wall and parts of the east and west walls of the kitchen were built on the original chimney foundation. These excavations also located step foundations at the southeast comer of the kitchen, at the former location of a 19th-century door, and a support or retaining wall built beside the original chimney. Apparently no excavation occurred inside the kitchen foundations at this time.

During the 1967 excavations, under the direction of Noel Hume, the entire interior of the kitchen was excavated. This revealed two brick floor sequences and several features cutting into a clay layer which seemed to represent the earliest floor in the structure. A rectangular pit or root cellar filled with ashes in the early 19th century was located to the west of the hearth. Ashes and iron slag beneath the clay floor, evidence of John Brush's 9 gunsmithing operation on the property, indicated that the kitchen was not in existence during Brush's occupation. For a full description of these excavations, see Frank (1967).

Smokehouse

When the Restoration acquired Brush-Everard in 1928, a frame construction smokehouse, set on a shallow brick foundation, was standing to the east of the kitchen. Archaeological investigations conducted in 1946 revealed the brick foundations of a small outbuilding (8' 1½" x 8') between the Brush-Everard House and kitchen. The wood ashes scattered inside led to the interpretation of this structure as the original location of the smokehouse. It was hypothesized that the existing smokehouse east of the kitchen had originally been located on these foundations; and moved sometime in the 19th century. The frame smokehouse use was consequently moved back to its original and present day location on the west side of the kitchen.

Potting Shed or Office

The Frenchman's Map depicts a small wing on the south side of the Brush-Everard House. Attempts to locate evidence of this wing through excavation (1947) revealed the foundation of an outbuilding, but no addition to the main house. The purpose of this structure, measuring 16' 2" x 12' 3", was not determined, but in the present property interpretation is being treated as a gardener's shed. There was no indication of a chimney foundation on the structure, and the building has been reconstructed in accordance with these findings. It may be important to note here that in Maryland, buildings which housed 10 documents were often constructed without fireplaces (Kandle 1984), perhaps indicated its original use as an office.

Laundry

Twenty nine feet north of the present brick kitchen, archaeological excavations uncovered the brick foundations of an outbuilding similar in size to the kitchen and containing a large chimney on its north end. Archaeology indicates that, like the kitchen, the building was originally 20' 4" NS in length; with a later addition constructed to the south. The building was interpreted as a laundry, perhaps on the basis of its large fireplace. The date of its construction is not known.

Wellhouse and Dairy

A well, 3'0" in diameter, was located 23' north of the laundry. Although the well head foundation was of modern construction, the brick well lining appeared to be colonial. Although the archaeological excavations of 1946/47 did not define the location of a dairy on the Brush-Everard property, a small dairy (9 EW x 9'NS) has been reconstructed immediately north of the laundry.

Palace Power Plant and Pond Area

This structure, measuring 40' EW x 20' NS, is located on Lot 172, at the comer of Spotswood and Scotland Streets. Built in 1933, the building housed boilers for use in 11 heating the Governor's Palace. Although specific reference to an organized archaeological excavation at that time could not be located, later memos (dating to 1946) bear evidence to a small amount of digging which occurred on the lot. When questioned in 1946 about the work (which apparently took place at or near the time of the boiler plant construction), no one at the firm of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn could remember details of the excavation. The boiler plant was reconstructed, apparently relying on the Frenchman's Map for dimensions of the 18th-century building which had once stood there.

Located to the east of the Palace Power Plant and bordering on Scotland Street is the reconstruction of a colonial pond. Archaeological excavations were conducted in this area by James Knight in 1946 in order to locate the old silt lines of the pond. These excavations revealed a brick dam running east-west at the northern edge of the pond, with a small outbuilding foundation located at the western edge of the dam. A 6" wide opening in the dam wall suggested the former presence of a water wheel or a mill in the dam. Various letters and memos concerning this dam and the possible interpretations of the site were written in the late 1940s/early 1950s. No agreement could be reached about the possibility of the small outbuilding being a shop or millhouse, and it was finally reconstructed as a privy. The privy was built on the location of the original outbuilding foundations.

1987-1989 ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESULTS

A number of archaeological deposits and features of interest were recovered during the recent excavations at Brush-Everard. Following is a brief summary of these findings and their current interpretation. These interpretations are subject to change as artifact analysis and final report writing take place.

The 1987-89 archaeological excavations were actually conducted on portions of three colonial lots: Lots 164, 165, and 166. Only Lots 165 and 166 were associated with the Brush-Everard property in the 18th and 19th centuries. As currently reconstructed, the fence separating the Brush-Everard property (lots 165 and 166) from that of the adjacent property to the south (Lot 164) has been incorrectly located. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the property boundary was actually located 20' to the north, as discovered by Noel Hume's 1967 excavation around the Brush-Everard kitchen. For that reason, two significant discoveries: five trash pits associated with Dr. Gilmer and a 19th century slave house, actually related to the owners of lot 164 in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Pre-House Period (Middle Plantation Period 1633 - 1699)

Although historical documentation suggests that the 1622 palisade ran through the Brush-Everard property, the archaeological excavations on the property did not show any evidence of this feature. Only two features dating to the Middle Plantation period were found (Figure 3).

13Borrow Pit

One feature, north of the present house, consisted of a large circular hole, approximately fifteen feet in diameter, excavated into the clay subsoil. This pit had been left open to partially silt in, and was later filled with yellow clay. Very few artifacts were found in the pit fill, and included only non-datable artifacts, such as animal bone and pipestems.

14At the present time, it is believed that the pit may have been excavated in the 17th century as a borrow pit for the recovery of clay for brickmaking. The hole was left open, silting in to a depth of about eight inches, until it was later deliberately filled with clay, possibly when John Brush excavated the cellar for his house after purchasing the lot in 1717. The stratigraphic position of the pit, sealed by an early 18th-century layer, and cutting through sterile soil layers, suggests the 17th-century date assigned to the creation of the feature. Borrow pits, sometimes dug near the site of 17th-century structures, were often used as garbage dumping areas for the households (Edwards 1987). The lack of artifacts recovered from this pit suggests that the structure for which these bricks were intended did not stand nearby.

Slot Fence

A second Middle Plantation feature, a slot fence, was discovered on the southern portion of Lot 165, south of the garden shed. Portions of this fence, running from southwest to northeast, had been discovered in 1967, running under the kitchen and smokehouse. Similar slot fences have been discovered on various 17th-century sites including Wolstenholme Towne (Noel Hume 1979), Nansemond Town in Suffolk (Luccketti 1988) and along the Hampton River (Edwards et. al. 1989). These fences were constructed by digging a narrow ditch about a foot deep. Planks were placed upright side by side in the ditch and then soil was packed around them to secure them in place. Such slot fences were used to keep animals from gardens or yards (Edwards et. al. 1989:92). There were no artifacts recovered from the slot fence at Brush-Everard.

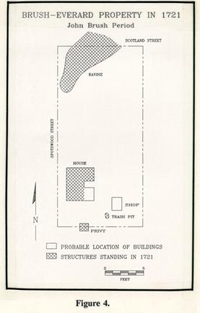

John Brush Period, 1717-1727

John Brush constructed a house on Lot 165 within two years after purchasing land from the City Trustees. Tree ring dating on original timbers in the house confirmed this, dating the last year of tree growth as 1718 (Heikkenen 1984). The house, a modest 44' x 20' story and a half clapboard structure, contained two rooms downstairs separated by a central hall. According to dendrochronology done at the Brush-Everard House in 1984, Brush constructed the north wing of the house shortly after 1720 (Heikkenen 1984). Figure 4 shows Lots 165 and, 166 as they are believed to have appeared during Brush's ownership of the property.

Archaeological excavations on the lot have not uncovered the foundations of an early kitchen on the property, so it is possible that the first kitchen on the property was in the basement of the house. The 1967 excavations revealed possible evidence of a ground-laid sill

Figure 4.

16

structure under the present kitchen (Frank 1967). Significant amounts of debris from John Brush's gunsmithing operation located in this area, both from yard scatter and within a privy and trash pit, suggests that this possible structure may have been his shop.

Figure 4.

16

structure under the present kitchen (Frank 1967). Significant amounts of debris from John Brush's gunsmithing operation located in this area, both from yard scatter and within a privy and trash pit, suggests that this possible structure may have been his shop.

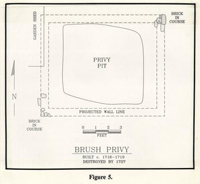

Privy

An unexpected discovery was made on the south end of the property at the end of the second field season. The truncated remains of a small (8' x 10') brick foundation outbuilding, representing a privy, which had been missed by earlier archaeological work on the property, were uncovered (Figure 5). This feature is the only 18th-century example of

Figure 5.

17

a privy yet discovered in Williamsburg. The structure, which contained a 4' deep underlying pit (6' x 5'), had been built after 1717 and destroyed by 1727 (Figure 6). Although the bottom of this pit contained organic waste, it was primarily filled with household garbage and gunsmithing debris from the John Brush occupation of the property. The numerous gun related artifacts recovered from this tightly dated assemblage will allow a detailed study of John Brush's gunsmithing operation in the early 18th century.

Figure 5.

17

a privy yet discovered in Williamsburg. The structure, which contained a 4' deep underlying pit (6' x 5'), had been built after 1717 and destroyed by 1727 (Figure 6). Although the bottom of this pit contained organic waste, it was primarily filled with household garbage and gunsmithing debris from the John Brush occupation of the property. The numerous gun related artifacts recovered from this tightly dated assemblage will allow a detailed study of John Brush's gunsmithing operation in the early 18th century.

The short use span of this building, which appears to have been constructed by John Brush when he acquired the property and abandoned less than ten years later, may be explained by a boundary dispute. The building straddled the property line between Brush's Lot 165, and lot 164, owned during most of this decade by William Levingston. The property boundary was represented by a long standing fence line discovered during the 1967 excavations. Numerous repairs to the fence were evident, attesting to its long life, with artifacts recovered from the holes suggesting that it was constructed after 1730 and stood until at least 1850 (Frank 1967). Several postholes and repairs, along this fence line, cut through the privy fill. Although no evidence of a boundary dispute has been located in the York County records, it is possible that Levingston, or later owner Archibald Blair may have wanted the building removed since it encroached on their property.

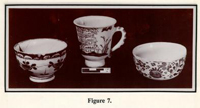

The quality of the ceramics and tablewares recovered from the privy suggests that Brush, a middle class artisan, enjoyed a much higher quality of life than previously thought. The ceramics from the privy included English delftware tablewares and teawares, including one blue handpainted Chinoiserie cappucino cup (Figures 7 and 8). These ceramics, plus

Figure 7.

19

the listing of a tea table in the 1727 inventory of John Brush's estate, indicate Brush's participation in the rituals of tea taking. Fragments from two Silesian stemmed wine glasses, a style popular in the 1720s, were also recovered and attest to Brush's acquisition of expensive and elaborate table glass. A number of whole wine bottles, including four pint bottles were recovered from the fill of the privy (Figure 9). Why these bottles, which were normally reused until broken, were discarded whole, is a mystery.

Figure 7.

19

the listing of a tea table in the 1727 inventory of John Brush's estate, indicate Brush's participation in the rituals of tea taking. Fragments from two Silesian stemmed wine glasses, a style popular in the 1720s, were also recovered and attest to Brush's acquisition of expensive and elaborate table glass. A number of whole wine bottles, including four pint bottles were recovered from the fill of the privy (Figure 9). Why these bottles, which were normally reused until broken, were discarded whole, is a mystery.

Performing pollen and parasite analysis on the soil layers filling the privy revealed interesting information about the diet and daily fives of the Brush household. Seeds and pollen from plants such as broccoli, blackberries, French parsley, potatoes, and capers, testify to the varied diet of the family, while the presence of intestinal parasites suggests that the household may not have enjoyed the best of health (Reinhard 1988, Mrozowski n.d.). The parasite eggs, which included human whipworm and intestinal roundworm, were from species that are transferred by contact with human excreta (Reinhard 1988). This privy provides us with the first documented evidence of the unsophisticated sanitation practices of Williamsburg's early 18th-century citizens. Such intestinal complaints were common in colonial Virginia. Landon Carter frequently records his slaves suffering with worms in the mid-18th century (Greene 1965).

What were the possible causes of these types of ailments? Steve Mrozowski, an archaeologist working in the Boston area, has suggested that the use of human fecal material as fertilizer on gardens could be one cause for the spread of such parasite problems. The virtual absence of 18th-century privy foundations in Williamsburg, plus the recovery of chamberpot fragments in trash pits and in open ravine areas suggests that the majority of human waste was being disposed of in the yards and other accessible places.

Ravine Fill

Excavations were conducted in 1987 and 1988 on the northern portion of Lot 16. Although Knight's excavations had not revealed traces of any buildings in this area, it was felt that perhaps a post construction building, of the kind easily missed Knight's 21 trenching techniques had once stood in this area. It seemed that this location, at the corner of Spotswood and Prince George Streets, would have been a prime location for a building of some kind, although this area was shown as vacant on the 1781 Frenchman's Map. What excavations did reveal were the remnants of a natural ravine which extended into the property from the north. Traces of this ravine are still evident today in the horse pasture directly east of the Governor's Palace. Throughout the 18th century, this ravine was used as a garbage dump by the owners of the Brush-Everard property. Traces of household activities, as well as architectural renovations on the property were evident in the ravine fill (Figure 10).

22The Brush ravine layer contained largely garbage generated within his household, with a small scattering of debris from his gunsmithing operation. As will be discussed later, the majority of the industrial waste was concentrated directly south and east of the house. Fragments of twenty different ceramic objects were recovered from the Brush period ravine fill. The majority of the ceramics were English delftwares (55%), ranging from table and teawares to ointment pots. Surprisingly, an English white salt glazed stoneware coffee pot and a Chinese porcelain plate were also found, suggesting Brush's acquisition of high quality ceramics. The ceramics from the ravine reinforce the data recovered from the privy that Brush's lifestyle was more comfortable than previously believed. Fragments of four delft fireplace tiles, decorated in blue, suggest a delft fireplace surround, and leaded window cames indicate the use of casement windows somewhere on the property during this early period.

Interim Period 1727-1756

Gilmer Trash Pits

During both 1967 and 1988 excavations on lot 164 (now partially contained within the Brush-Everard property), five trash pits from Doctor Gilmer's occupation of the lot were excavated. These pits varied in size from 4' x 4' to 11' x 12' and were filled with household and apothecary shop garbage during the period from 1735 to 1757. The majority of the ceramics (55%) were English delftware drug jars and ointment pots, in both handpainted and undecorated forms (Figure 11). These items were certainly associated with Dr. Gilmer's apothecary shop which stood on the corner of Nicholson and Palace Streets.

23

Figure 11.

Other items from the shop included glass pharmaceutical bottles, pin tiles, and large bottles known as carboys, which were used for storing carbolic acid and other liquids. At least sixteen Piermont water bottles were also recovered from the trash pits; Piermont water, bottled in Germany (Noel Hume 1972:61), was advertised for sale in Gilmer's shop in Virginia Gazette advertisements from this time period.

Figure 11.

Other items from the shop included glass pharmaceutical bottles, pin tiles, and large bottles known as carboys, which were used for storing carbolic acid and other liquids. At least sixteen Piermont water bottles were also recovered from the trash pits; Piermont water, bottled in Germany (Noel Hume 1972:61), was advertised for sale in Gilmer's shop in Virginia Gazette advertisements from this time period.

Doctor Gilmer was also living on Lot 163, in the house constructed between 1716 and 1718 by William Levingston. Some of the garbage from the trash pits was generated by his household. In 1752, Dr. Gilmer wrote a letter to Mr. Walter King, a Bristol merchant. In that letter he mentions the set of china that King is sending to Mrs. Gilmer, and the closet which Gilmer is having constructed to hold it (Brock Notebook). Two matching blue and white Chinese porcelain plates recovered from the trash pits represent some of the china owned by the family (Figure 12). The Gilmer family also owned Chinese porcelain teawares in the forms of cups, saucers, tea bowls, and slop bowls, Tableware 24 forms included seven plates, a platter, and four punch bowls. Chinese porcelain made up nineteen percent of the Gilmer household ceramics, and was contained largely within the most recently filled trash pit on the lot.

In addition to the porcelain, a number of ceramics of English manufacture were included in the trash pits. The sequencing of the trash pits and the preliminary analysis of these ceramics indicates that the Gilmer family was eating off of blue and white painted delft tablewares, replacing these with molded white salt glazed plates and Chinese porcelain around the mid-18th century. Teaware forms were also found in the Gilmer garbage in white salt glazed stonewares and in decorated English delft.

Post Structure

Some details about the appearance of the property during the 18th century were revealed through archaeology. One of the purposes of the 1987-1989 excavation was to locate remains of several outbuildings shown on the Frenchman's Map but not uncovered by James Knight during his 1947 excavations.

25The construction dates on the reconstructed Everard outbuildings, such as the laundry, power plant and the garden shed are not known, although the Frenchman's Map, drawn in 1781 shows five outbuildings standing to the east of the house. One of these was the kitchen, which was constructed around 1730. It is likely that among the others was included the reconstructed laundry, a stable or coach house (reconstructed as the power plant), and a possible slave quarter. Construction dates for the reconstructed buildings will probably never be determined, since the archaeological trenching of 1947 and subsequent reconstruction destroyed all archaeological evidence useful for dating.

Although an extensive area was excavated directly south of the power plant, in the projected location of one of the structures seen on the Frenchman's Map, the remains of an early 20th-century house, and a large number of modern disturbances had unfortunately destroyed all 18th-century soil strata in this area. The 1988/1989 excavations focused on the location of the other structure depicted directly north of the reconstructed laundry on the Frenchman's Map. Excavation in this area revealed a brick walkway dating to the early 19th century, a spread of late 18th-century household artifacts, and several structural postholes indicating the former presence of a building.

Traces of a post-seated structure were uncovered on Lot 166, directly east of the reconstructed dairy and well. Six large postholes, spaced at five foot intervals, denoted a building with dimensions of 15' east-west and an unspecified distance north to south. The building was oriented with its long end facing Palace Street. It also appeared to run underneath the reconstructed laundry and for this reason, complete excavation of the post structure was not attempted. The stratigraphic composition of the soil and the artifacts 26 recovered suggest that this building was constructed in the second quarter of the 18th century, perhaps during Elizabeth Russell's or William Dering's occupation of the lot. It is not known at this time what function this building served. Later repairs to the postholes suggest that this building could have been standing during Everard's ownership of the property and was depicted on the Frenchman's Map.

Although no hearth was located within the extent of the excavations, one could exist within the portion of the building not yet excavated. If heated, it is possible this building was a slave house; if not, it could be a stable. Although complete excavation of the building was beyond the time and budget constraints of the project, the dimensions and possible function of the building could be determined through further excavation.

THOMAS EVERARD PERIOD, c. 1751? - 1781

Although documentary records do not place Thomas Everard on Lots 165 and 166 until 1779, it is believed that he purchased them around the time that he sold his house lots on Nicholson Street to Anthony Hay in 1756 or possibly as early as 1751. Extensive renovations to the house were undertaken by Everard during the time that he owned the lots. It is also believed that Everard added the house's elaborately carved front staircase and paneled hall.

Although traces of the outbuildings shown on the Frenchman's Map were destroyed by later construction, there is some evidence concerning how Everard was using other 27 portions of his property. Directly north of the house was a fenced section of land. Since no evidence of structures or planting beds were found in this area, it is suggested that Everard, and perhaps earlier residents were using this area as pasture for his horses and other livestock. North of this fenced area, at the northern end of Lot 166, the natural ravine or gully found there continued in use as a garbage dump by the household. Three soil layers currently believed to relate to the Thomas Everard period were excavated in this ravine. The earliest, and most productive layer was formed during the early period of Everard's tenure, and contained an unusually rich deposit of domestic debris (Figure 13). The large quantity of food-related bone from the household, as well as other plentiful organic remains, in the form of seeds, fish scales, crab claws, and egg shell fragments, will provide significant information about the 18th-century diet of both Everard's family and his slaves.

Sometime in the early 1770s, Thomas Everard decided to fill and level the ravine bisecting the north end of his property. To do this, he fined the gully with a layer of yellow clay, raising the ground level on Lot 166 between two and eighteen inches. This clay was typical of the underlying subsoil which is found at a depth of two to four feet below ground surface. It is suggested here that the origin of this clay may have been from the excavation 28 of a cellar. Although it has been suggested that Everard's renovation of the house took place soon after he purchased the property, evidence from the recent archaeological excavations suggests that this renovation did not take place until the early 1770s, when he ordered quantities of nails, paint, and window glass from John Norton and Sons (Norton).

A slight slump or dip in the yellow clay layer was filled with garbage during the latter years of the Everard occupation. Soon after this, a driveway of crushed coal was placed over the filled ravine. It is possible that this driveway led to the building shown fronting on Scotland Street on the Frenchman's Map. Figure 14 shows the Brush-Everard property as it is believed to have appeared during Everard's tenure.

POST-18TH CENTURY

Polly Valentine House

Documentary evidence suggested the presence of a mid 19th-century slave house on the property, just south of the garden shed. Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman's published account of Williamsburg life describes in detail the Tucker family mammy, a woman by the name of Polly Christian (Coleman 1934). Polly was a gift to Nathaniel Beverley Tucker from his half brother John Randolph of Roanoke. When Polly married Jim Valentine sometime around 1840, a house was constructed for them, where they lived and raised a family until the outbreak of the Civil War. Archaeological excavations conducted on the Brush-Everard property in 1967 by Ivor Noel Hume and those done in 1988 did reveal evidence of a pier supported frame structure, measuring 15' x 25' (Figure 15). This type of pier construction building became a common form of slave housing in the mid-19th century and was described in numerous period volumes on plantation management The wooden frame house rested on brick and stone piers and contained a substantial brick

Figure 15.

30

hearth. Remnants of five piers remained, allowing the dimensions of the house to be calculated. It was probably a one room structure, with sleeping or storage space above. Archaeological evidence seems to suggest that the house was destroyed during the Civil War, perhaps during the two-year Union occupation of Williamsburg.

Figure 15.

30

hearth. Remnants of five piers remained, allowing the dimensions of the house to be calculated. It was probably a one room structure, with sleeping or storage space above. Archaeological evidence seems to suggest that the house was destroyed during the Civil War, perhaps during the two-year Union occupation of Williamsburg.

The Polly Valentine House is the only known house built expressly for slaves in Williamsburg at any period during the 18th or 19th centuries. At the present time, an Anthropology graduate student is preparing her master's thesis on a comparison of the Valentine site with other slave quarters from the same time period. Her search of the extensive collection of the Tucker-Coleman papers at the College of William and Mary should provide additional information on Polly Valentine and other Tucker family slaves. The excavation of this structure, plus the excellent Tucker family documentation should combine to provide important information on the material life of mid 19th-century slaves.

Jefferson Bone Handle

One discovery of particular interest was a bone handle, believed at first to have been from a toothbrush (Figure 16). Actually part of a small knife, the handle bore the

Figure 16.

31

incised inscription "TH JEFFERSON". Thomas Jefferson, in his capacity as the second governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia, lived in the Governor's Palace between 1779 and 1780. It is probable that this item was left behind when Jefferson moved the capital to Richmond, and during the process of cleaning the Palace property after its destruction in the late 18th century, the handle was moved to the Brush-Everard property next door.

Figure 16.

31

incised inscription "TH JEFFERSON". Thomas Jefferson, in his capacity as the second governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia, lived in the Governor's Palace between 1779 and 1780. It is probable that this item was left behind when Jefferson moved the capital to Richmond, and during the process of cleaning the Palace property after its destruction in the late 18th century, the handle was moved to the Brush-Everard property next door.

A search of the York County files did reveal two other York Country residents by the name of Thomas Jefferson. There is, however, no conclusive evidence that either of these men ever lived in Williamsburg. Additionally, each of these men died before the future president had ever been born. Although it is possible that this handle could have belonged to one of the other Thomas Jeffersons, its appearance in an early 19th century soil layer and its proximity to the Governor's Palace lead us to conclude that the handle actually belonged to President Jefferson.

Examination of the bone handle by members of the Collections Department revealed that the handle was not typical of 18th-century toothbrushes, and was more likely the handle to a comb, small brush or some other item from a men's toilet kit. The engraving, consisting of one quarter inch triangular block letter, appears to have been done by a jeweler and not Jefferson himself (Figure 17).

SUMMARY

Although still preliminary, some conclusions can be drawn from the recent excavations at Brush-Everard. John Brush, the first owner of the property, did operate his gunsmithing practice on the Palace Green lots he purchased in 1717. Although this shop has not been located, the amount of gunsmithing debris recovered from the 1967 and 1987-89 excavations suggests that his shop was in the vicinity of the present kitchen. Analysis of the gun parts found in the privy and ravine will provide a better understanding of the kinds of work that Brush was performing in his capacity as a gunsmith.

Brush is also responsible for constructing the house, perhaps much in the form that it is shown today. Although the techniques of archaeological excavations used in the 1940s destroyed evidence that could have determined when the southeast wing of the house was constructed, performing dendrochronology on original timbers in the northeast wing shows that it was constructed soon after 1720. It is possible that Brush constructed the matching southeastern wing as well.

The ceramics and fine table glass recovered from a Brush period privy and trash layer in the ravine suggest that John Brush, a middle class artisan, was actually enjoying a much higher quality of life than had been previously suspected. The leaded crystal wine glasses discarded before 1727, were of a type popular in the 1720s. Expensive Chinese porcelain and English delft teawares indicated that Brush and his family were participating in the fashionable ceremony of tea drinking. Artifacts from the recently excavated 1730s root cellar or storage pit on the Grissell Hay site will provide an interesting comparison 33 between the material possessions and diet of Archibald Blair and John Brush. In addition to the fancy ceramics and glass, dietary information recovered from the privy deposits shows that the family was enjoying a varied diet, and using imported spices to season their foods.

The next major occupant who left traces on the property was Thomas Everard. Although documents indicate that he was performing renovation on his property, archaeological analysis has not progressed far enough at this point to make any statements about the work Everard was doing. Since a series of modern disturbances had destroyed a major portion of the area shown as containing the Frenchman's Map outbuildings, archaeological research was apparently not successful in recovering the remains of a slave house on the property. Further analysis may reveal that the post-seated structure located to the north of the laundry may have housed slaves.

Although conclusive evidence of 18th-century slave housing was not found on the Brush-Everard property, the household garbage which can be associated with the Everard household can partially be attributed to Everard's slaves. Since Everard's household contained a greater number of slaves than members of his own family, it stands to reason that some of the garbage on the lot was generated by the slaves. A few items, such as beads and coins which were worn as personal adornment, seemed to be slave related. It is felt that detailed analysis of the Everard material win provide some information on the material possessions and diet of the Everard slaves.

The Gilmer trash pits were interesting in that they provided the most complete assemblage of 18th-century pharmaceutical material ever excavated in Williamsburg. In 34 addition to this, the trash pits provide us with the opportunity to chart the consumer practices of the Gilmer family. This series of pits, created over the twenty year tenure of the Gilmer household, show the increasing expenditures through time on quality ceramics. This information fits in nicely with the evidence from Gilmer's letters in the early 1750s that the renovations in his dining room made "it a tolerable room for an Apothecary" (Brock Notebook). Through gaining increasing financial security through time, Gilmer had reached the stage in his life where expenditures could be made on embellishing his home with elaborate marble chimney pieces and wooden wainscoting.

Although during the third quarter of the 18th century, a number of wealthy and influential persons lived around the Palace Green, the area began to decline after the moving of the Capitol to Richmond and the burning of the Governor's Palace. This is evident in the moving of the former Levingston House, adjacent to the Brush-Everard property, in the 1780s, to its present position (much modified) facing Market Square as the Tucker-Coleman House. Another vivid reminder of the decline of this area was the 1988 discovery of a mid-19th century slave house which had been constructed along the Green.

Although excavation has been completed on the Brush-Everard property, analysis of the three seasons worth of artifacts has just begun. It is expected that the results of this analysis will add substantially to the information now available about the occupants of the property and how it changed over time. A complete report on this project can be expected in early 1991.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Manuscript Volume in the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

- 1934

- Virginia Silhouettes: Contemporary Letters Concerning Negro Slavery in the State of Virginia. Richmond: The Dietz Press.

- 1987

- Archaeology at Port Anne; A Report on CL7, An Early 17th Century Colonial Site. Unpublished report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1989

- Hampton University Archaeological Project. Volume 1: A Report on the Findings. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1967

- Brush-Everard House Kitchen and Surrounding Area. Block 29, Area E, Colonial Lots 164 and 165. Report on 1967 Archaeological Excavations. Report on file at the Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1965

- The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall, 1752-1778. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville.

- 1984

- The Years of Construction for Eight Historical Structures in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, as Derived by the Key-Year Dendrochronology Technique. Report on file at the Department of Architectural Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1984

- Personal communication.

- 1988

- Untitled Paper. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Society of Virginia, Hampton, October 1, 1988.

- n.d.

- Personal communication. 36

- 1979

- First Look at a Lost Virginia Settlement. National Geographic 155 (6):735-767.

- 1972

- A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. New York: Alfred Knopf.

- 1988

- Analysis of Latrine Soils from the Brush-Everard Site, Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia. Report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1956

- Brush-Everard House; Block 29. Colonial Lots 165, 166, 172. Report on file at Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.